Five Children on the Western Front by Kate Saunders is a deeply old-fashioned novel. It is quite brilliant as a result, and was one of my favourite reads in the year it was published.

In my previous Book Dissection I looked at a very contemporary first person voice in Cosmic by Frank Cottrell Boyce. In my second outing, I want to look at a passage from Five Children and examine what makes it so delightfully old-fashioned while at the same time powerfully affecting. For anyone who hasn’t read it, I promise no spoilers, but you really must get a copy, and sharpish.

The novel is inspired by the ‘Five Children and It’ series by Edwardian writer E. Nesbit. In the original books a family of children are granted wishes by a sand-fairy, including one, very short scene, in which they are able to travel to the future and visit a family friend, the Professor. Five Children on the Western Front imagines what that future might be. Here’s a section taken from the Prologue:

‘I say!’ Robert called from the window. ‘The street’s full of motor cars! Does everyone have a motor car in 1930?’

Cyril hurried over to look; both boys were fascinated by motor cars and dreamed of driving them.

The cars down in the street were long and sleek and moved like the wind.

‘I’m cold,’ the Psammead announced. ‘And the sensors at the extreme end of my whiskers are simply screaming damp. Take me back to my sand.’

‘Don’t!’ the professor sighed. ‘Don’t let me undream you just yet.’

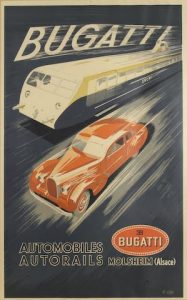

We start with a charming idiom that drips crumpet butter and cricket on the green: ‘I say!’. It’s upper class Edwardianism at its best. There’s a guiding principle in historical novels that the language register of the characters should avoid anachronisms (“‘OMG!’ Robert called” would have a very different tone!), and Saunders is sticking to that principle. This continues with the quaint description of the traffic as ‘motor cars’. The setting, a city in the first half of the twentieth century, is established. But there are actually two time periods at play here – 1905 and 1930 – Saunders has to give us an impression of both. So, as well as the slang, we also get that evocative description of the cars a few lines later, they are ‘long and sleek and moved like the wind.’ This reads like a description of those beautiful Art Deco transport posters; so the 1930s are present in the streets outside.

Cyril’s reponse to Robert is one of the most old-fashionedly constructed sentences in the piece. Proper Old Skool.

We’re told he hurries over because ‘both boys were fascinated by motor cars and dreamed of driving them.’ This is written from the point of view of an external narrator using an omniscient perspective. Once a very common stylistic choice in children’s fiction, but now tossed on the scrap heap like an old East 17 album, or a torn shell suit. We are in both Cyril and Robert’s heads at the same time. This God’s-Eye perspective, moving at will severally and singularly between characters really gives Edwardian flavour to the novel. [In an aside here, to think about the psychic distance used, this joint-thought is successful because of the gentle gradation used to achieve it: Robert speaks, an external narrator reports it; Cyril moves to stand beside Robert, the external narrator reports it; the external narrator sees them side-by-side and reports both their thoughts. Lovely. I was asked last time whether authors know they are using all these techniques, I said no, but in this instance I bet it was very deliberate.]

Let’s jump to that wonderful interjection of the attention-seeking, whiny Psammead. How do we know his character is so disagreeable? We are shown it. Nature is evoked to describe the cars which move ‘like the wind’. The Psammead subverts this with ‘I’m cold’. It’s great bathos. Then we get that most Drama Queen of sentences, stuffed with all the rhetorical bells and whistles he can muster: alliteration (“extreme ends”), sibilance (“simply screaming”), assonance (“extreme…screaming”), and consonance (“simply..damp”). He might as well yell ‘Shut up and pay attention to me!’

The Professor’s reply is subconsciously troubling for the reader. He says ‘Don’t!’ and that exclamation mark suggests he shouts, but in fact we’re told he’s sighing. Then that word ‘undream’, a neologism that wrong-foots us. It feels a bit too modern, as though this safe Edwardian adventure isn’t at all what it seems.

But no spoilers.

I’ll just say that the rest of the prologue had me biting back tears. In a good way. Five Children on the Western Front is an old-fashioned treat that’s as fresh as anything out there.

Five Children on the Western Front, Kate Saunders, 2015, Faber and Faber, ISBN: 978-0571323180

This post originally appeared on MG Strikes Back blog.

0 Comments